Pollinators, cover crops and pies a-plenty at Small Potatoes Farm field day (Aug. 3, Minburn)

On Saturday, Aug. 3, a diverse crowd of about 50 people gathered outside the packing shed at Small Potatoes Farm, a 10-acre farm near Minburn owned by Rick and Stacy Hartmann, to hear about a particularly salient topic: protecting our native pollinators, and what farmers and landowners can do to support and provide habitat for these beneficial insects.

The Hartmanns cultivate 3 acres of certified organic annual fruits and vegetable crops in any given year, with production focused on their CSA market. The day couldn’t have been more perfect: sunny, low-humidity and milder than one would expect for the first weekend of August, and Rick and Stacy’s lush, well-tended farm was a delight and a privilege to explore. Like the native bees they had come to hear more about, the attendees represented some of the diversity of faces and ethnicities, regions and farming systems that comprise Iowa’s agricultural landscape. In addition to a group of immigrant Nepalese and Bhutanese farmers brought by Lutheran Services of Iowa, based in Des Moines, some attendees had come from Iowa City, Decorah and even as far away as Ithaca, N.Y. (a Cornell student enrolled for the summer in ZJ Farms’ Farming Institute program).

Field day attendees read follow along with Don Lewis' presentation on a handout about the research results.

Common Pollinators in Iowa Melons and Squash: The field day started with a discussion led by Don Lewis, extension entomologist with Iowa State University, highlighting the differences between three of Iowa’s main types of pollinators: bees, wasps and flies.

- Bees tend to be very hairy with branched hairs; they have FOUR wings; their antennae are low and “elbowed” (they bend at a segment); and they have broad, hairy legs; and their legs tend to be loaded with pollen in a pollen-carrying part of their anatomy called a “scopa.”

- Wasps are usually less hairy or hairless; have FOUR wings; their antennae are long and not elbowed; their legs are narrow and hairless; and they don’t carry pollen;

- Flies are also usually less hairy than bees or hairless; they have TWO wings; their antennae are short and not as obvious to the viewer; their legs are narrow and hairless; and, like wasps, they do not carry pollen.

Pollinator Study: First of its Kind in Iowa: The discussion then segued to a summary, led by Don and colleague Mark Gleason, professor of plant pathology and microbiology at ISU, of a recently completed two-year, three-state study that sought to determine what insects are pollinating cucurbit crops (melons, squash, cucumbers and pumpkins) on commercial farms in Iowa, Kentucky and Pennsylvania. Small Potatoes Farm was among the eight Iowa farms and 24 total farms involved in the study, which ran from 2010 to 2011. To survey the pollinators, researchers used two methods: 1). bowls of varying colors filled with liquid (different colors attract different pollinators), and 2). a device called a “Bee-Vac,” which is a small capture device that uses gentle suction to suck the pollinators off of flowers. Bee bowls were placed in cucurbit fields (on Small Potatoes Farm, sampling was done in his cucumber and squash fields) for one week at a time to get a snapshot of the larger pollinator community, while Bee-Vacs sampled only pollinators in cucurbit flowers.

The results surprised all involved. “What was amazing was people used to think that the honeybee, Apis Mellifera, is what we need for pollination,” Don said. “But over two years of sampling with Bee-Vacs, only two individual honeybees were caught. It was the squash bee, Peponapis pruinosa, that was the most important for pollination.” In that time, more than 50 individual squash bees were captured from cucurbit flowers. In the colored bowls, Lewis said researchers found a 41 different species of bees on Rick and Stacy’s farm alone. “The diversity of species was amazing,” he said. “This was the first study of its kind in Iowa, so we didn’t have anything to compare it to.”

Rick said the information revealed by the pollinator study was essential for farms to have. “I hope it’ll be a direction of research that starts to take off.”

What Does Iowa’s Pollinator Diversity Look Like?

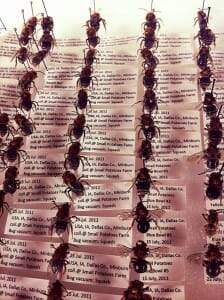

After hearing the summary of the pollinator study, attendees were able to browse Rick’s pollinator collection — an impressive library of all the pollinators collected on his farm during the course of the study. They were neatly arranged in several boxes (at least five):

|

|

Don Lewis had also brought a display box showcasing a range of Iowa’s native bees and other pollinators:

Solitary Bees Predominate: As the photo illustrates, Iowa has many different types of bees. Most are in the “solitary bee” category, which defines bee species where each female builds and provisions her own nest. Unlike the more familiar “Social Bee” species that build large colonial hives (honeybees and bumblebees are both social bee species), solitary bee nests are narrow tunnels with just a few brood cells. Females provision their nests with nectar and pollen, and live just a few weeks after their nests are completed. While most people picture the honeybee when thinking about bees, they are actually newcomers to the United States, brought by European settlers. Originally, they were invasive species. Solitary bees, however, are native to the U.S., and are much more diverse.

Within the solitary bee grouping, several smaller sub-groups exist. Some of these sub-group names are pretty self-explanatory. There are are “Stem and Cavity Nesting” bees, which comprise leafcutters (3 species), sweat bees (1 species) and mason bees (5 species). There are “Ground Nesting” bees, which comprise mining bees (14 species), sweat bees (32 species), long-horned bees (16 species) and “small” carpenter bees (12 species). This diversity would likely be a revelation for most Iowans, and is hopefully a compelling reason to do more to steward these populations.

Importantly, Don said that crop rotation does not seem to negatively affect the bees’ ability to find their host crops. Not all bees are beneficial, though! Some bees, like Tripeolus lunatus, is a parasitic bee that eats other bees and lays their eggs in other bees’ nests. The vast majority of bees are beneficial, however.

Pollinator Discussion in the Field: After the talk by the shed, the field day moved out to the field, where Rick talked about some of the things he and Stacy do on their farm to encourage native pollinators. Some of these practices include:

- Planting buffer strips that contain native plants, like compass plants and other wildflowers. The mix the Hartmanns planted is from a Michigan study, and includes plants that have different flowering times so there are flowers (and thus habitat and food for pollinators) throughout the season. The Xerces Society, a non-profit group devoted to conserving invertebrate species, has a list of plants that are beneficial to pollinators, and also works with regional nurseries to sell approved “Pollinator Conservation Seed” mixes.

- Planting native lawns. Rick commented that he “doesn’t know why people are so opposed to creeping Charlie,” but speculated that it’s because our culture has been conditioned to think perfectly uniform, European-style lawns are what constitutes an attractive, well-groomed and desirable look.

- Avoiding synthetic pesticides. Rick said he doesn’t use synthetic chemicals, and if he has to spray a pyrethroid-based spray (a natural insecticide made from the pyrethrum family of Old World plants) on cucumbers, he only does so after bees have finished feeding and departed for the evening — and he always avoids spraying the flower parts. Sometimes, he simply uses soapy water on squash plants. Rick estimated he probably spends no more than about $80 per year for natural insecticide

- Succession planting and cover cropping, practices that help to break up pest cycles (without the need for pesticides) and proffer other food sources for pollinators.

- Planting edge-of-field flowers with longer lasting blooms. Rick has been planting zinnias, which are not only pretty to look at but also flower constantly throughout the season. However, he commented that he recently learned that due to extensive domestication and breeding for showiness, zinnias might not offer as much nutrition for pollinators as previously thought and he might need to look at other plants for his field edges.

- Providing overwintering habitat. Rick and Stacy have planted elderberry shrubs and American cranberries and nurtured willow and other trees, which provide leaf litter, nesting cavities and other features that can help beneficial pollinators survive and Iowa winter.

These practices have helped Rick and Stacy nurture a robust population of pollinators on their farm. Rick said that, while they’ve sometimes had fruit that was “imperfect because of incomplete pollination,” they have never had to bring outside pollinators onto the farm. “Our populations of damaging insects are pretty much moderated,” Rick said. “All this diverse habitat definitely helps.” As an example, Rick recounted how one year, the Small Potatoes Farm had an “extremely large” aphid population — into the thousands, potentially — that covered the trunks of the willow trees. “One day the ladybugs showed up and within three days, they eliminated every one of those aphids. It was pretty incredible.”

Pests are Host-Plant Specific: One of the attendees asked whether the buffers might harbor crop pests, and thus attract unwanted insects to the farm. Don replied that most crop pests are host-plant specific and will only lay their eggs on one specific type of crop. Cabbage worms, for instance, will only lay eggs on plants within the broccoli family; they won’t eat tomatoes. Thus, the buffer strips were unlikely to become a haven for crop pests. He added that it wouldn’t help to eliminate insects found on plants that weren’t their main host crops. Even though the cabbage worm butterfly might eat some nectar from another plants, “it won’t help her much, and she was going to live anyway.”

Mark Gleason commented, by way of illustrating both the host-plant specificity of some pollinators and the need for more pollinator habitat, that monarch butterflies eat milkweeds and nothing else. “Their populations are down in Iowa because of RoundUp-Ready corn and beans.” Taking up this point, Don added that, because many native bees and pollinators are smaller than honeybees, a smaller dose of pesticide can be devastating. “If you have one hive of 150,000 squash bees and you treat it, you lost them all,” he said.

Rick said his biggest pest problems have come from the crop farms around him. “I had tens of thousands of hornworm beetles come within a few days, because the corn and soybeans got too dry,” he said. “We’re a little green island in a sea of brown.”

PART 2: Cover Crop Discussion: After the pollinator portion of the day, Rick led field day attendees to look at two different cover crop plots he is testing through Practical Farmers of Iowa’s Cooperators’ Program.

Sunn Hemp: The first is a field planted exclusively with sunn hemp, a tropical legume native to India that has been used for millennia. Rick planted sunn hemp as a summer cover crop on June 28 by broadcasting by hand and disking with a small disk. Despite the lack of moisture much of Iowa experienced in the late spring and early summer, the sunn hemp germinated well — comparable to buckwheat. “It was almost three to four weeks in the field with no rain,” Rick said. “I like that, because in the summer you can’t always count on timely rains.” PFI purchased the seed from Green Cover Seed in Nebraska.

Rick said he usually plants cover crops at twice the standard seeding rate, because he does not grow cover crops to harvest seeds and he wants to “maximize the benefits of cover crops, such as increasing organic matter and fixing nitrogen.”

|

|

One of the current setbacks to using sunn hemp, however, is that there’s not much seed available. “So to make this practical, we would need to get seed costs down,” Rick said.

Cover Crop Mix Plot: The next stop was back on the other side of the farm, to look at what Rick said was “that messy field” planted with a cover crop mix consisting of: cow peas, sunn hemp, buckwheat, millet, radish, forage soybean and sorghum sudan grass. While Rick was enthusiastic about the sunn hemp-only field, he was less glowing about this plot, mostly because the weather challenges had set back plant growth, so that the buckwheat was already flowering while most of the other plants were not as far along.

With this cover crop plot — also part of PFI’s on-farm research project — Rick will look at nitrogen production, and also, after it gets tilled in, whether the cover crop mix has any effect on weeds that germinate later.

Rick’s Advice on Cover Crops: Kate Edwards, who runs Wild Woods Farm in Solon, then said she was interested in doing some mid-season cover crops and asked Rick for his advice. Rick said that he tries to get three cover crops off his cover crop plantings. “A year ahead of time when I look at my rotation schedule for the year and the next year after that, I decide what I’m going to plant and where,” Rick said. “I make a map of the field. That drives my cover crop decisions.

“I tell my CSA customers: ‘My Purpose isn’t to maximize what you get every week; my purpose is to have a functional whole farm.'”

Aster Yellows in Garlic: Someone then asked about Rick’s garlic, and he talked for a bit about how he — like many other Iowa vegetable and garlic farmers — was hit hard by aster yellows disease in 2012, and how climate variability last year (especially the early spring) allowed an uncommon disease to cause outsized damage. The disease actually affected garlic growers across the Midwest in 2012, Rick said, although infestation in garlic is usually rare. In fact, he said the last time widespread aster yellows in garlic occurred was in the 1930s. Last year, the unusually warm spring allowed the aster leafhopper — the vector of the disease — to emerge much earlier than usual, and the only green things up at that time were gralic and small grains. “It just devastated the boutique garlic industry in the Midwest.”

Rick said that some might argue aster yellows in 2012 was just a fluke, but he stressed that over the past 140 years there has been a clear shift to more extreme weather and unpredictable weather patterns. “There’s a clear tendency toward more extreme weather, more water in the summertime and more water at one time,” he said. “It’s really hard to anticipate how to control pests when you have them pop up at unusual times.” This reality is just another reason why doing a range of practices to protect and promote beneficial insects and pollinators is important.

X.B. Yang, extension soybean specialist at ISU, was in attendance and commented that due in part to climate change, “long-term planning for big row-crop farmers is harder, so they spray more.” Rick agreed, and said both planning and the realities of more spraying were problems for produce farmers as well.

“I’ve been lucky,” he said. “I rely on the courtesy of my neighbors. Last year when my garlic, leeks and carrots started turning yellow, I thought I’d been sprayed, and I was really mad. But then I started hearing about other people with yellow garlic.” Through the reports that started coming in on the PFI email discussion list, he learned that the issue was widespread and thankfully — at least in regards to his relations with his neighbors — not due to pesticide drift.

Rick then mentioned Practical Farmers’ garlic testing research this year in response to the outbreak. Several Iowa farms with damaged garlic seed were tested; results are pending — so check back with us soon if you’re curious!

Lunch, courtesy of Emilyrose’s Sweetie Pies: The group then wended back to the packing shed for a delicious meal of savory and sweet pies made by Emily Rose Pfaltzgraff, a PFI member from Hampton who just recently launched her new business, Emilyrose’s Sweetie Pies. The savory pie was filled with produce from several PFI farms, including MoGo Organic Farm, Middle Way Farm, Echollective and Small Potatoes Farm, and the sweet pie was a delectable mix of red raspberries, blackberries and apples baked to an ideal consistency. Everyone seemed to enjoy this fun and creative meal. If you’re interested in having custom-cooked pies for your next holiday, wedding, family gathering or other event, you can contact Emilyrose’s Sweetie Pies at (715) 557-2397 or iowasweetiepies@gmail.com.

|

|

|

|

Stacy and Rick demonstrate their systems for picking zucchini in the field (Rick is cautious to distribute the weight so delicate squash skins aren't scratched) and washing.

Part 3: Packing Shed Practices: After a relaxed lunch, Stacy led the final segment of the field day, discussing the farm’s packing shed practices, systems, efficiencies and answering any questions from the crowd. While Rick is lord of the fields, Stacy is queen of produce prep and packing, and she emphasized that having good systems in the packing shed is critical. Their current systems and wisdom are the culmination of years of practice, problem-solving, tweaking and refining. For instance, Stacy pointed to some mounted bag pullers affixed to one of the shed’s walls. “How we lived without this before, I don’t know,” she said, stressing that “efficiencies are important.”

Other examples of Stacy’s efficiency-focused practices:

- Getting as much dirt off the produce in the field as possible, or cutting the tops of bad beet greens in the field rather than at the packing shed. This cuts cleaning time in the packing shed and helps make washing more efficient — which is important to Stacy, because she washes virtually all the farm’s produce. “Onions might be the exception,” she said. “I don’t like to put dirty produce in CSA boxes.”

- The washing station is actually located just outside the shed. While there might be some occasions during the season when she or staff get rained on, or when it’s chilly and hands get cold, this is another efficiency because it keeps the inside of the packing shed dry, tidier and leaves more room to spread out CSA boxes for packing.

- Harvesting produce that’s more time-consuming to wash and dry (like lettuce, which is a multi-step process) the day before CSA deliveries (Tuesday and Friday), and avoiding over-harvesting on those days to make washing plus box-packing less onerous.

- Cleaning often along the way, rather than all at the end. “When it gets too chaotic in here — too many boxes everywhere, too much mess — that’s when we make mistakes. I’d rather have a little tidying up to do and then get back to work, than have to spend two hours cleaning up later.”

Other topics Stacy canvassed ranged from discussion of how she and Rick handle distribution (they each go solo on separate days to Ames or Des Moines) to how she and Rick plan what varieties to plant each year (they survey customers at the end of each growing season) and Stacy’s approach to packing CSA boxes (she lays all the boxes out on tables, and is particular about packing quantity). Stacy also discussed a neat customer- and efficiency-focused practice she and Rick started to help minimize potential food waste once customers get their produce home: a “sharing box” where Stacy places a sundry assortment of produce that was either leftover from a previous week, too soon to be plentiful enough for equal distribution in CSA boxes, over-plentiful, less plentiful due to weather, etc. Customers can exchange an item from their CSA box with an item they prefer in the sharing box — a great idea all around that also is an easy way to add a bit more flexibility into the CSA operation.

Those in attendance seemed content to keep asking questions and listening, but the time quickly slipped away and it was time to head home — and let Rick get back to harvesting! As if it weren’t an illuminating enough field day on a lovely and well-tended Iowa farm, these two little guys were stars of the show, quickly endearing themselves to all in attendance at their irresistible cuteness:

|

|