Creating Pollinator Habitat at Mustard Seed Farm

Well, it certainly has taken me a just little longer than planned (self-directed sarcasm intended!) to write this summary of the Mustard Seed Community Farm field day (held July 25) — but it was such an excellent event, that the knowledge deserves to be shared!

The title of the event, “Establishing On-Farm Pollinator Habitat,” is an accurate summary of what the field day was all about. Mustard Seed, an 11-acre vegetable farm operated by Alice McGary and Nate Kemperman northwest of Ames, has made pollinators and their well-being a key part of the farm’s land stewardship practices. This work has included prairie restoration on the farm, and growing many species of pollinator-friendly plants around the entire perimeter of the farm, as well as throughout the property.

(Read more about Alice and Nate’s prairie restoration efforts on their blog.)

The benefits are mutual: These plants — which include species like wild bergamot, purple coneflower, spiderworts, butterfly milkweed, buckwheat, mints, sunflowers and many others — attract native bees and other pollinators, which then help to pollinate the farm’s crops. The plants also provide a buffer for the farm, while creating nesting and habitat spaces for pollinators and other wildlife.

(To see a photo gallery of images from the field day, click here to jump to the end of this post).

Pollinator Research Project

To get a better handle on the diversity of pollinators visiting the farm, Alice and Nate participated in a PFI research project looking at how many bee species visited different habitats on the farm throughout the growing season (May-August).

(Note: Mustard Seed is continuing this project with University of Northern Iowa).

The broader pollinator project with University of Northern Iowa features 11 sites around Iowa, of which Mustard Seed is one. The project seeks to map bee species found in areas with native vegetation compared with corn and soybean areas located within a 1 kilometer radius.

UNI graduate student Andrew Ridgeway explained the reason is because “we want to map out and see if there’s a correlation between the number of bees and the type of land nearby.”

At Mustard Seed, the project included four habitats: lawn, a pepper field, a prairie garden and a newly established prairie seeding.

Differently colored cups were set out in the various habitats, which Mustard Seed farm team members checked four days each month (spread out over the whole month). Insects found in the cups were collected, frozen and sent to Iowa State University, where a graduate student identified them.

WILL OSTERHOLZ, a Mustard Seed farm team member, explained: “We did the project because bees are so important, especially on a vegetable farm. We wanted to know how many bees we had, and also how habitat types — even on a small farm of this size — play a role.”

“Even a pollinator-friendly island in a sea of corn and beans can make a difference, especially for migratory insects.” — ALICE MCGARY

Project Results

- All four Mustard Seed habitats in the study (lawn, pepper field, prairie garden and prairie seeding) attracted numerous individual bees (121 to the lawn, 404 to the peppers, 186 to the prairie garden and 242 to the prairie seeding).

- The greatest diversity of species, however, was found in the prairie garden: It attracted 26 species of bees. Diversity was similar in the pepper field (16 species) and prairie seeding (17 species), and lowest on the lawn (12 species).

- Alice commented that they didn’t notice any particular seasonal pattern in the overall number of bees. “Some days we got a lot of bees, other days not as many.”

- But Andrew added that there was a noticeable shift in which type of bees were predominant. “You can really see a transition in bee species over the season. Earlier in the season there were lots of green bee species. Then bigger bees show up, and there are fewer green bees. You can really see changes in the bee community.”

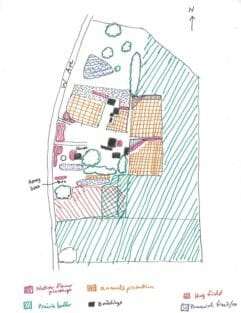

Map of different habitats at Mustard Seed Community Farm. (This is a PDF file! Inside, you’ll also find: 2014 results from Mustard Seed’s pollinator project, data charts, and Mustard Seed’s lists of best pollinator plants and best pollinator species).

The image to the right is a map, hand-drawn by Will Osterholz, of the various habitats and production fields at Mustard Seed Community Farm. It’s a map of the whole farm, not just the areas included in the project.

Click the image, and you’ll also access a PDF packet that you can download featuring project results from 2014, and Mustard Seed’s lists of best pollinator plants and best pollinator species.

PFI Research Report: To view the Practical Farmers research report (“Baseline Bee Data Collection at Two Farms”), click here.

Questions from Attendees

1). Are you worried about competition between native bees and honeybees?

ANDREW: “No, we’re not worried about competition. Smaller, native bees have a flight range of maybe 60 meters, whereas honeybees can travel a mile or more. So one issue [for native bees] is if there’s nothing around for them to eat.

“And keep in mind: It takes, on average, about 18 visits from a honeybee to successfully pollinate a plant, versus about eight visits from a native bee. If you take a couple of years to actively manage for native bees, you won’t have to do much else [to ensure your crops are pollinated]. You won’t have to truck in honeybees or worry about who will supply them. With native bees, you’ll have a great [pollination] source.”

NATE: “I’ve seen honeybees only on certain plants. So I’m not worried about native bees crowding them out, or vice versa.”

ALICE: “Honeybees are better at going from apple flower to apple flower, which can be good when those are in season. But native bees are better at having more variety, getting up early and working later. I think it’s good to have both honeybees and native bees.”

2). How do you attract more native bees?

ALICE: “Think about the different types of nests they make when planning habitat. Some like stems, others are ground-nesting, others like woodpiles. They’ll find flowers, but they need a place to sleep and spend the winter.”

Some Key Points and Takeaways

#1). Crops Need Pollination. “People sometimes forget this, because there are so many corn and soybean acres in Iowa. Pollination is especially important for a vegetable farm. At Mustard Seed, we’ve also got fruits, berries and herbs. Not all crops need pollination — but those crops will do better with good pollination. Other crops require pollination.” — ALICE

(Note: Even though corn and soybeans don’t require insect pollination, these crops can provide pollen and nectar to feed bees — and many bee species forage in row crop fields during the window when those crops are flowering).

#2). Small Efforts Matter. “Even a pollinator-friendly island in a sea of corn and beans can make a difference, especially for migratory insects.” — ALICE

#3). Diverse Plantings = Diverse Pollinator Community. “Many bees are generalists, but some bees specialize. For instance, squash bees only pollinate squash plants.” — AI WEN, an ecologist with UNI who is leading the pollinator project there. She explained that having a variety of plants would offer something to attract a diverse population of pollinator species.

Click here to return to the top of the post.