Field Day Recap: Grass-Based Dairy Farming and Value-Added Cheese Production

In mid-August, 60 people visited Lost Lake Farm to learn about one of Iowa’s newest dairies. Kevin and Ranae Dietzel built a milking parlor and cheesery in 2016 – where 21 cows are milked and where that milk is turned into artisan cheese. “We make cheese to add value to milk on the farm,” said Kevin, who explained that adding value is necessary to make this small-scale, grass-fed operation profitable.

Kevin got his start making cheese when he and Ranae raised one dairy cow that produced far too much milk than they could drink. Kevin experimented at home, which lead him to take cheese-making courses in Vermont and Wisconsin, fueling his dream of becoming a dairy farmer. Eventually, Kevin and Ranae found a farm outside of Jewell, IA to establish their dairy.

Lost Lake Farm is named after Lake Cairo, which was a 1,500 acre lake that was drained at the turn of the century to turn into agriculture land. The farm is situated around the ancient lake bed, which is comprised of Blue Earth soil and contains high amounts of carbon. This land once was a reed-collecting route and campground for the Meskwaki Indians.

The cows

The dairy herd is comprised of several breeds – Brown Swiss, New Zealand Friesian, Normandy and Jersey crossbreds. Kevin is happy with the performance of his cows and plans on narrowing down his genetic diversity over the next 20 years. In early August the herd was milking, on average, 17 pounds per cow. Since the milk is turned into cheese, the protein content of the milk is what matters, not the amount of fluid milk produced. Cows are milked once per day, as a result of labor constraints, but eventually Kevin would like to milk twice a day. Calves are left on their mothers for three months, which makes once a day milking possible, since some of that milk is going straight into the calves when cows are making the most milk.

The grass

Cattle are forage-fed year round; they graze a mix of perennial and annual forages and eat hay and baleage over winter. Kevin has experimented with annuals such as sorghum-sudan grass and cowpeas and has seeded strips of festulolium, meadow brome, orchard grass, meadow fescue, white and red clover, alfalfa, forage chicory and birdsfoot trefoil – all which are grazed and made into baleage, depending on growth. Kevin practices what he calls “management intensive flex grazing,” moving cattle every 12 hours, and resting pastures for 21 to 42 days. With only 21 cows, “we’re not exactly mob grazing because we don’t have the number of cows needed,” explained Kevin. Watch the clip below to see cows moved from an alfalfa field to a sorghum-sundan grass field.

To keep grass in a vegetative state, Kevin thinks, “In the future I will make hay on about 1/3 of the pastures in the first rotation or use custom grazing for 1 to 2 months in early spring, if there are animals in the area to be custom grazed.” Kevin adds, “I have read and heard many people talk about “grazing tall”, where the animals graze through quickly, just biting off the tops of the grass, then the grass re-grows from that point. In my experience, this just makes the grass head out faster, and leaves more of the less desirable grasses ungrazed. I think grazing tall can work, if the pasture is clipped or there is a second herd following the lactating herd that can graze or trample it down further.” Next year he wants to implement a leader-follower system when milkers graze first, followed by youngstock, heifers and dry cows. This would eliminate the need for clipping and save fuel and time. Kevin prefers to use cows over tractors.

The cheese

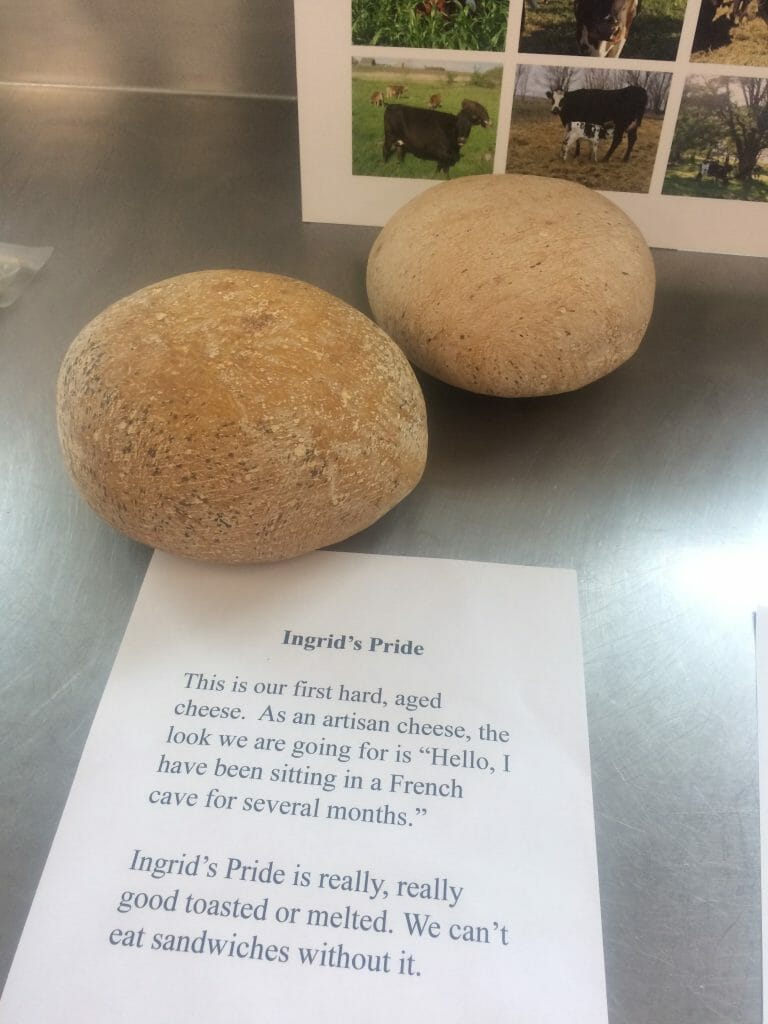

Cheese is made two to three times per week, and each time it’s a 23 hour process that starts at 3:30 in the morning. The high quality grass-fed milk and hard work that’s put into it can be tasted in their cheese – a provolone style called Ingrid’s Price, and fresh mozzarella and curds. Kevin is currently perfecting his recipe for alpine style cheeses and camembert, which will be available for purchase later this year. For a detailed description of the cheese making process, listen to Kevin’s interview with PFI staffer Nick Ohde in an On-Farm podcast.

Part of what imparts flavor in their cheeses are the biodynamic farming principles Kevin and Ranae follow. These principles guide farmer’s thinking to focus on the farm as one organism and Kevin says that following these principles helps capture the quality and complexity of the flavor of the milk. Through artisan cheese, Kevin is able to create a product that embodies terroir – “the taste of place.”

The four hour field day gave attendees a chance to see cattle moved to a new pasture, the milk parlor, the cheesery and share a delicious potluck lunch. After we left, Kevin realized he didn’t have enough time to talk about important aspects of their journey to becoming a certified dairy and cheesery. Here he shares those thoughts:

Business and marketing

Kevin and Ranae took a non-traditional angle in securing money to make this dream come true. They took loans from individuals, as well as from two different business development organizations. “We organized our company as an LLC so that we could take on investors. This took time and lawyer fees to accomplish. The advantage is that we got startup funds without a requirement to pay back debt. The disadvantage is that, should we become profitable, we must share those profits. We will have to buy out the investors in the future if we want to own 100% of the company – but presumably their shares will be worth more in the future than they initially bought in at, so the tradeoff is in profit sharing and having to pay for the capital gains we have created. Without it we would not have been able to get the cheese business off the ground,” explained Kevin.

In regards to their marketing plan, Kevin said “Our plan was to start with mostly direct marketing, but as the timing worked out, we started having cheese to sell in the fall when most of the direct marketing options were slowing down. This meant that we moved toward selling in retail stores more quickly than initially planned, which is good for having fairly stable sales numbers and being able to move product, but not great for margins since we get a wholesale price when we sell to stores. We are continuing to work every day to increase sales on all fronts. Most of our direct market sales are through farmers’ markets, which are great but time-consuming.”

Profitability and cash flow

Kevin offered insight to other beginning farmers. “We made a very thoroughly-researched and -calculated business plan and had many people review it. Most said it was the best, most thorough plan they had ever seen. Despite that, our first year has been a real eye-opener: production and sales have been more time-consuming and lower than projected, and expenses have been consistently quite a bit higher than projected. This is discouraging, to say the least. Let this be a warning to other beginning farmers still in the planning phase.“

Working with custom operators

“We are short on both time and capital, so spending money on farm equipment and time on operating (and repairing) that equipment is not feasible at this point in our business startup. We are lucky to have neighbors who are willing to help out when needed. Usually the prices we pay are based on the Iowa Farm Custom Rate Survey. A few times we have exchanged for helping out with something they needed help on.”

Kevin continued, “The advantage is this saves us time and the need to come up with the money to purchase equipment. The disadvantages are: we have less control over how things are done and when they get done. Despite paying market rates for the service, our small scale means it is still mostly a favor from them, and they have a lot of other work to do for their own field operations. Sometimes hay doesn’t get done in a timely manner because they are doing hay elsewhere, and the next good haying weather window is several weeks later, so our quality ends up not great.”

Thank you to the Dietzel family for opening up their farm and also thanks to Organic Valley and the field day sponsors: Hamilton County Soil and Water Conservation District, Iowa Farmers Union, Welter Seed & Honey Co., Wheatsfield Co-op, and Town & Country Insurance.